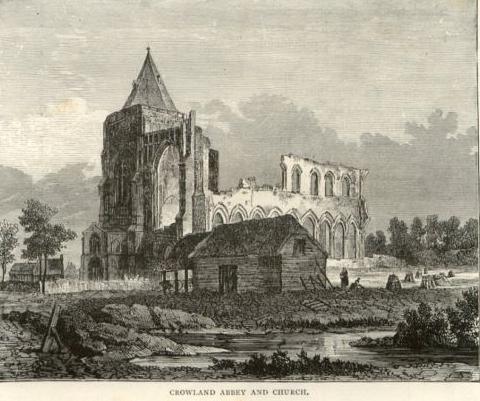

History of the Abbey of Crowland

Crowland Abbey was a monastery of the Benedictine Order in Lincolnshire, sixteen miles from Stamford and thirteen from Peterborough. It was founded in memory of St. Guthlac early in the eighth century by Ethelbald, King of Mercia, but was entirely destroyed and the community slaughtered by the Danes in 866.

Refounded in the reign of King Edred, it was again destroyed by fire in 1091, but rebuilt about twenty years later by Abbot Joffrid. In 1170 the greater part of the abbey and church was once more burnt down and once more rebuilt, under Abbot Edward. From this time the history of Crowland was one of growing and almost unbroken prosperity down to the time of the Dissolution. Richly endowed by royal and noble visitors to the shrine of St. Guthlac, it became one of the most opulent of East Anglian abbeys; and owing to its isolated position in the heart of the fen country, its security and peace were comparatively undisturbed during the great civil wars and other national troubles.

The first abbot (in Ethelbald’s reign) is said to have been Kenulph, a monk of Evesham; and one of the most notable was Ingulphus, who ruled from 1075 to 1109, and whose pseudo-chronicle was long considered the chief authority for the history of the abbey, though it is now acknowledged to be a compilation of the fifteenth century. At the time of the Dissolution the abbot was John Welles, or Bridges, who with his twenty-seven monks subscribed to the Royal Supremacy in 1534, and five years later surrendered his house to the king. The revenue of the abbey at this time has been variously estimated at 1083 and 1217 pounds. The site and buildings were granted in Edward VI’s reign to Edward Lord Clinton, and afterwards came into the possession of the Hunter family. The remains of the abbey were fortified by the Royalists in 1643, and besieged and taken by Cromwell in May of that year.

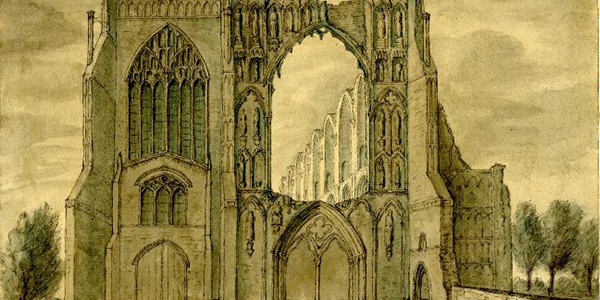

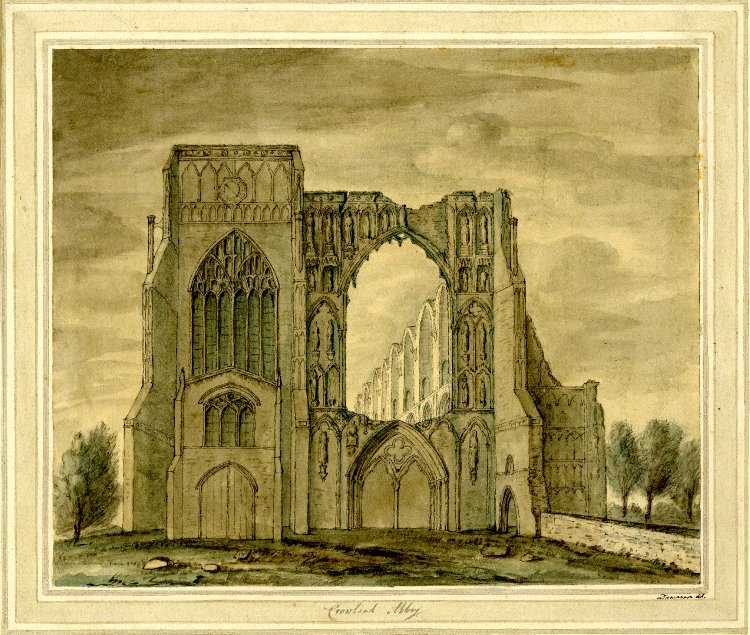

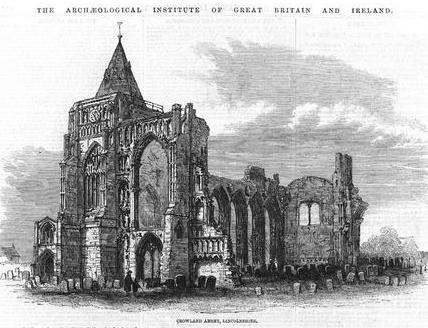

The abbey church comprised a nave of nine bays with aisles, 183 feet long by 87 wide, an apsidal choir of five bays 90 feet long, a central tower and detached bell-tower at the east end. The existing remains consist of the north aisle, still used (as it was from the earliest times) as the parish church; the splendid west front, the lower (twelfth century) and the upper part (fourteenth century) elaborately decorated with arcading and statues, it is thought in imitation of Wells cathedral; and a few piers and arches of the nave. Much careful restoration and repair has been carried out since 1860, under Sir Gilbert Scott, Mr. J.L. Pearson, and other eminent architects.

The bells of Crowland Abbey have a rich and colourful history, The first bells to be hung in Britain were in the belfry here. The length of the ropes is also remarkable as is illustrated here.

The Crowland chronicle associates the hanging of the bells with a miracle of Guthlac as described here:

At this period, there happened in our monastery a circumstance of everlasting remembrance, which some of the most intelligent, even, ascribed to a wondrous miracle. The greater bell-tower had been newly built in the western part of the church, in which it was intended that the bells before-mentioned should, by the skill of the carpenters, be hung. At this time it was not covered in at the very top, nor was it in any way closed by the intervention in it of any lower floor. Having put together, on the ground below, a certain machine for the purpose of winding and drawing, they endeavoured to fix in the summits of the walls an immense beam, held by ropes and pulleys, to act as a supporter of the whole work. By dint of great efforts on the part of those winding, the beam had been now raised nearly fifty feet from the ground, and was hanging poised aloft, when, on a sudden, the tackle proving unequal to the strain of such an immense mass, began to give way. At the same moment, the ropes burst asunder, and the beam, falling to the ground with a loud crash, broke the whole fabric to atoms that lay below. There seemed no chance of escape whatever for the men, nearly twenty in number, who were labouring below and were now placed almost at the very verge of death; nor would it have been of any use for them to fly, seeing that the beam in its length across equalled the square space between the walls. However, the Divine mercy instantly regarded them thus threatened by a peril so terrific, and smitten with the greatest consternation at so unlooked-for an event; for the breaking down of so vast a mass did not crush one of them, and its precipitate fall did not the slightest injury to a single individual. Oh instance of the Divine grace, deservedly to be lauded and extolled! Oh, how glorious, too, the merits of our father Guthlac! Who could possibly withhold himself from uttering the praises of God?

St. Guthlac's Pilgrimage